May 31, 2023

Sapiens Behavior

I’ve been thinking a lot about rational vs. irrational value swaps lately and where my platform-specific (or not) behavior falls on this plane. As a starting point, these ideas are centered on @cpaik definition of atomic value swaps in his frameworks document:

--

ATOMIC VALUE SWAPS

An Atomic Value Swap is the measurement of the sustainability of repeated core transactions in an ecosystem. Payment for goods or services is an example of an atomic value swap, one where cash is exchanged for an item or service. Both parties deem the transaction to be beneficial and therefore the transaction occurs. If the price of a product or service is too high, the buyer will not engage in the transaction.

Secular to secular (money/goods/services) atomic value swaps are easily understood by the market clearing price of the exchange. Secular to sacred atomic value swaps are significantly more complicated to understand as behavioral psychology tends to skew expected reactions from supply or demand to changes in the transaction.

This extends best to less tangible exchanges as a concept to understand non-monetary transactions. For example, asking for an invitation to a new product is exchanging fractional social indebtedness for a scarce resource.

The three questions that help me ring fence the atomic value swap in any situation are:

What is the value being delivered?

What is the perceived value of what is delivered?

How fairly compensated is the creator for value delivered?

--

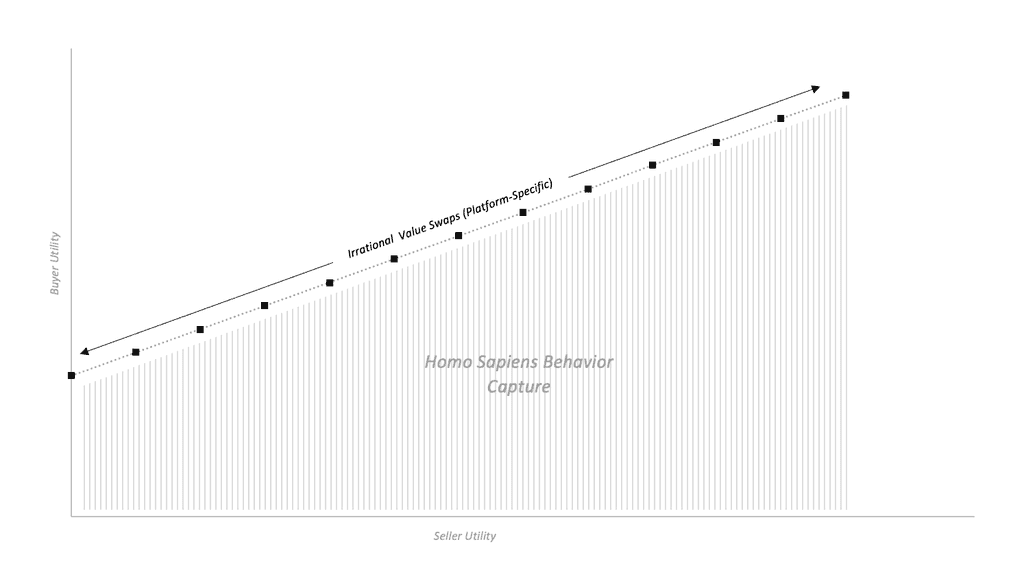

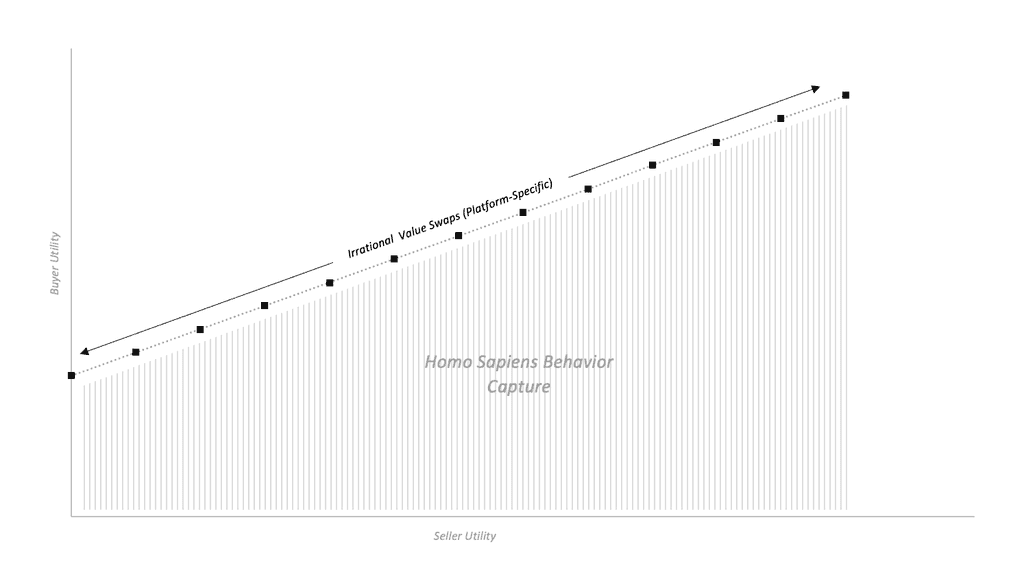

Most dominant platforms enable a value swap that is decidedly rational – one that occurs at least on a large enough scale to suggest that there is a clearing price which people are willing to accept in exchange for greater convenience, utility, access, pleasure, etc. In the simplest sense, a user gets something (X) back for what they give away (Y), where they perceive X and Y to be relatively equal. The transaction is fair.

There are other swaps of value which are best characterized as one-sided transactions (in which one party expects nothing or little in return), and if not entirely one-sided, very unequally weighted (highly favorable to one party vs. the other). It is not that these transactions are not fair (they could very well be fair in the mind of the user – the transaction might otherwise not occur), but they do not follow a strictly utility maximizing framework. What drives this type of irrational (and highly willing) behavior is powerful, and appears to be more feeling focused (a “soft” driver of behavior) vs. utility focused (a “hard” driver of behavior). I engaged in a transaction of this nature recently, which informs much of the reasoning I’m attempting to explain in this piece.

The team from Worldcoin was just in New York with one of their orbs (this is Sam Altman’s project premised on a vision for UBI / defi / identity verification in the age of AI). It is at once fascinating, logical and dystopian. Naturally, I wanted to see the orb for myself. World App launched the same week and I could hypothetically tie my identity via iris scan to my wallet. Within a matter of seconds, I conceded my iris and became a number in an index of hashes – for essentially nothing in return, zero utility (outside of the US, there is a token reward for the iris scan… though the tokens are worthless for the time being). I do not necessarily have concerns around privacy in the case of this transaction – the orb generates a unique encoding of the randomness of the iris and destroys the original biometric, aka the iris code is the only thing that leaves the orb. And any transaction in the future is a ZK proof that you are in the verified set, aka identity is never revealed. This is compelling when it comes to human attestation / proof of personhood in an internet increasingly run by AI / deepfakes / bots.

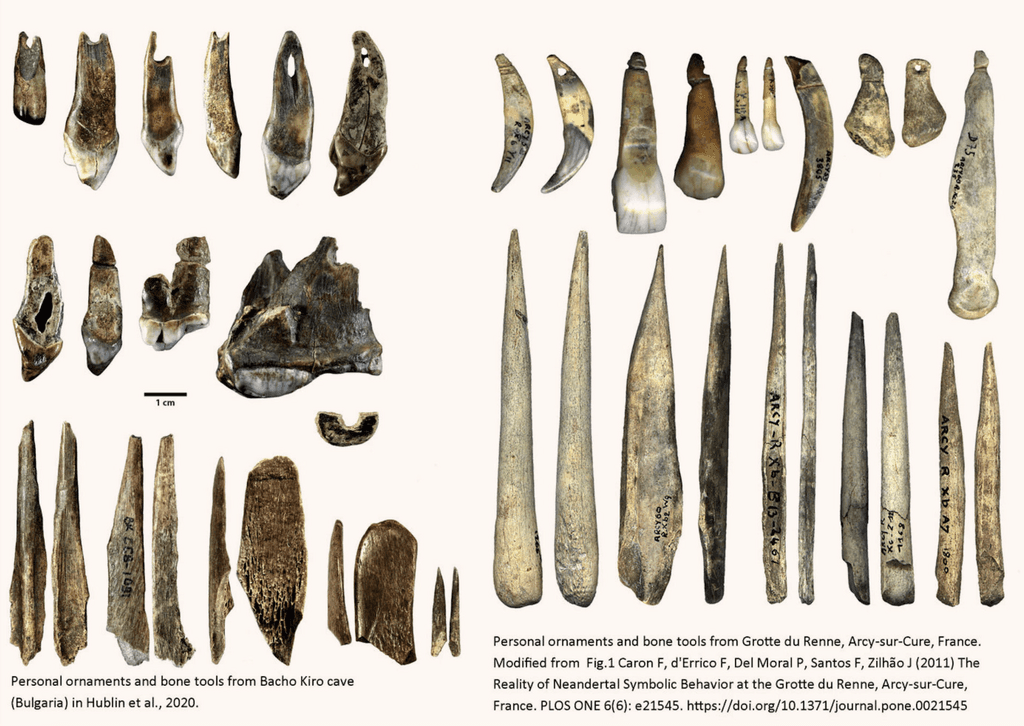

Where I did become increasingly concerned, however, was at my own behavior… how had I so easily engaged in a definitively one-sided value swap – one in which I derived little tangible utility yet willingly relinquished a highly personal, immutable aspect of my own identity. My best explanation of this behavior was something along the lines of tribalism, fear, curiosity and the allure of an aesthetically futurist hardware. None of which should logically justify an uneven swap of value. The crazy thing is I would make this decision again.

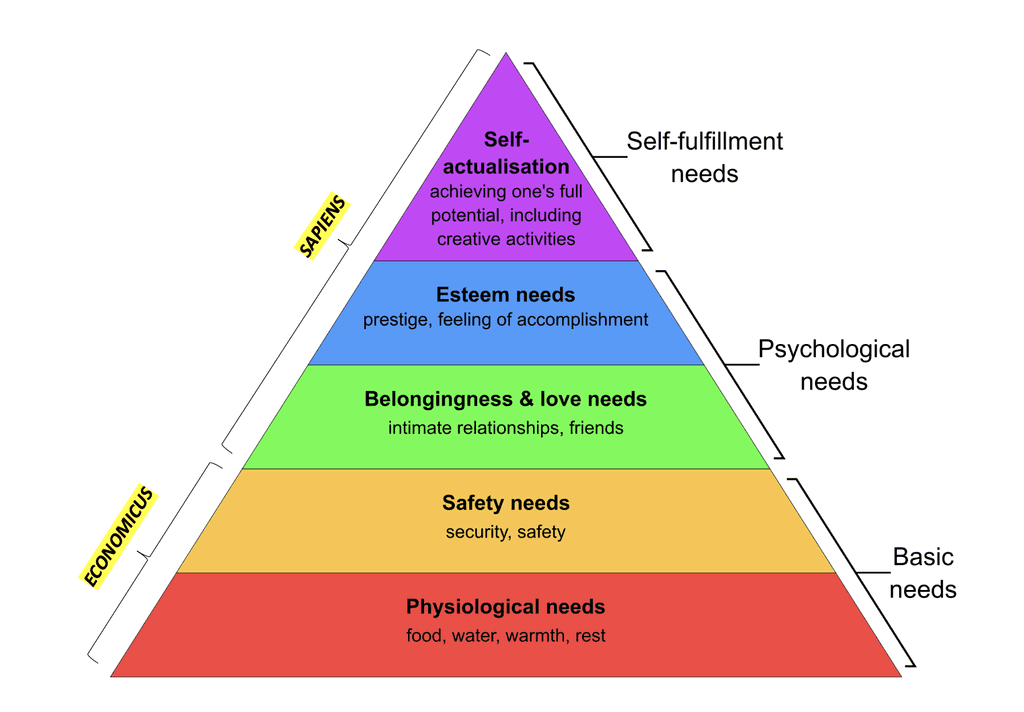

Homo Economicus vs. Homo Sapiens theory feels relevant here (and related to the secular vs. sacred concept as referenced in the frameworks document).

Homo Economicus: The figurative human being characterized by an infinite ability to make rational decisions. Narrowly self-interested, Homo Economicus assumes perfect utility / profit maximization.

Homo Sapiens: The figurative human being who is boundedly rational, constrained by limited memory and computational capacity. The decisions made by such humans are influenced by psychological, cultural, and emotional factors.

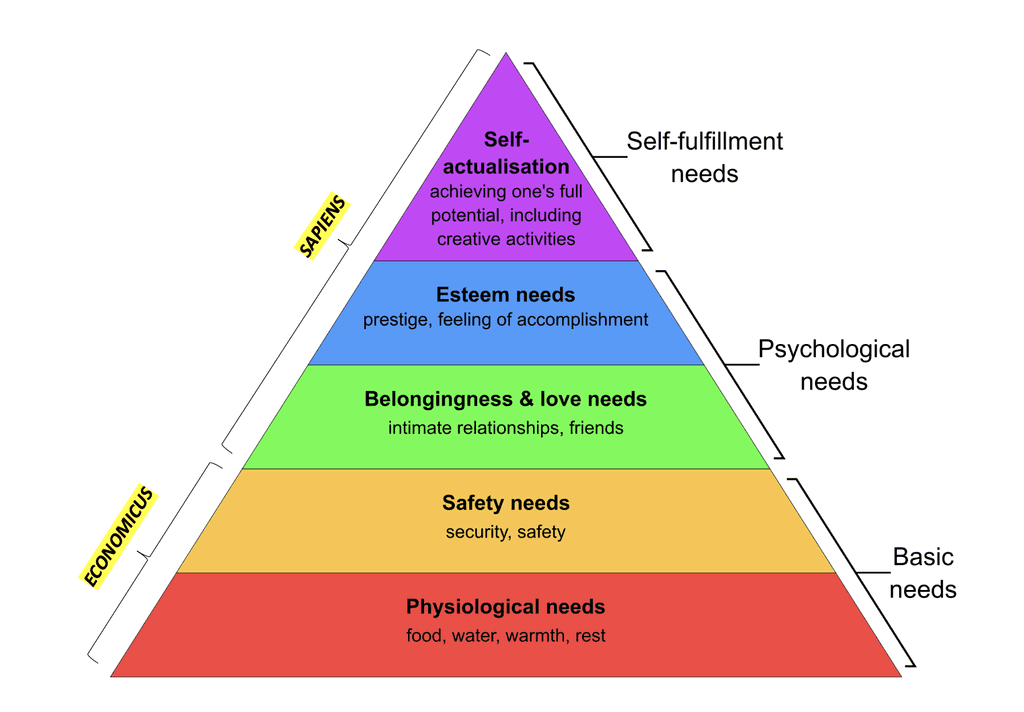

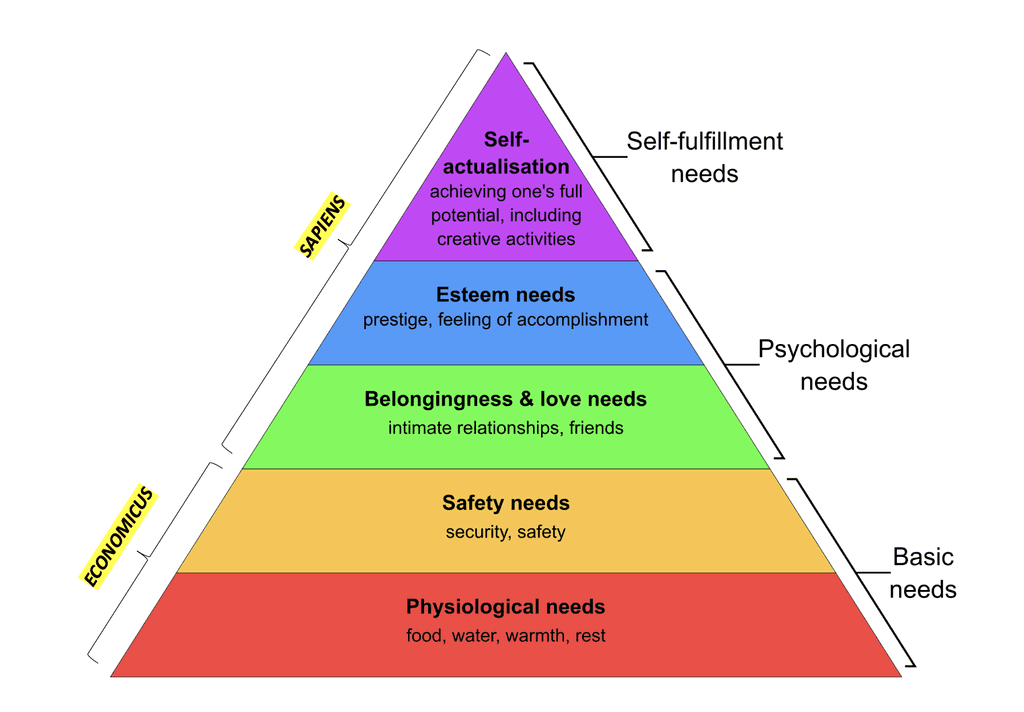

While Economicus is consistently rational, Sapiens optimizes for a utility that is less quantitatively direct – self expression, social adherence / social signal (where my Worldcoin exchange falls). I think this matches well with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs:

Some examples of Sapiens behavior on the internet:

Prospect theory / loss aversion: Suggests that people make decisions based on the perceived outcomes of those options rather than the actual utilities. I.e. social proof triggers fear of missing out, so sites show limited quantities of a product available.

Status quo bias (could fall under Prospect Theory): The tendency of people to choose the status quo, even though it may be less favorable than an alternative. People are more likely to stick with what they have instead of taking a risk and switching to something else. Algorithms deeply enable this.

Time preference: The extent to which people value current consumption over future consumption (and are willing to pay a higher amount for the same good). I.e. I am willing to pay more to have something delivered to me today, instead of in a week. Or advertisers optimizing for eyeballs / impressions instead of long-term brand building.

Devaluation of small things that are valuable in aggregate: Small (irrational) transactions which in isolation seem like no big deal, yet once added up are very meaningful. I.e. trading privacy for convenience until your data is everywhere on the web.

When everything is free / accessible / easy, humans will optimize for things other than pure economic utility. So as the cost of software goes to zero, companies must increasingly service Sapiens behavior. I’m not sure where Worldcoin sits on this scale – right now, it seems to be capturing Homo Sapiens behavior with the promise of delivering Economicus value later. We will see how this plays out. What I do not know is whether Sapiens behavior is unique to the human condition while Economicus behavior leans toward the behavior of a machine. How this dynamic starts to change with AI is a theme I am very interested in – I think some of the AI companionship activity (Character, Replica, GirlfriendGPT) hits on this, but not at an equal plane with the reactivity / irrationality of human emotion (not yet at least). Will machines eventually replicate the irrationality of man even if it is not utility maximizing?

According to Blaise Pascal, who you are likely familiar with if you have studied Pascal’s triangle, “the last step of reason is to grasp that there are infinitely many things beyond reason.” There is something to be said that one of the world’s greatest mathematicians / inventors, a type who most strongly prefers scientific / logical reasoning, acknowledges the beauty (and power) of Sapiens behavior, which does not follow the assumed logic of the universe, beyond a purely utility optimizing approach. Lex Fridman has a good podcast on this called Reality is a Paradox (Love and Math).

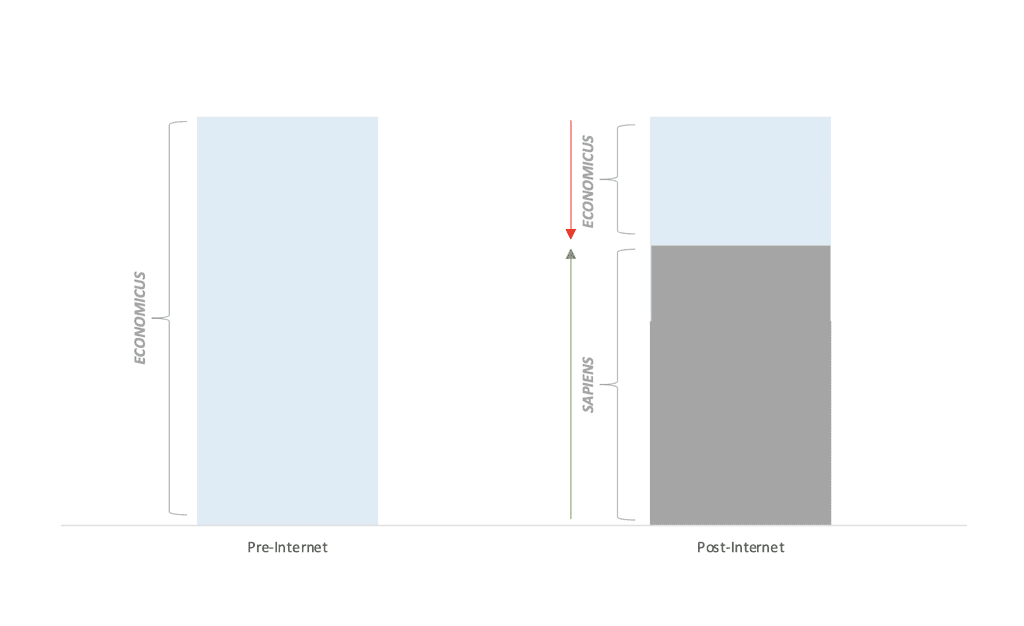

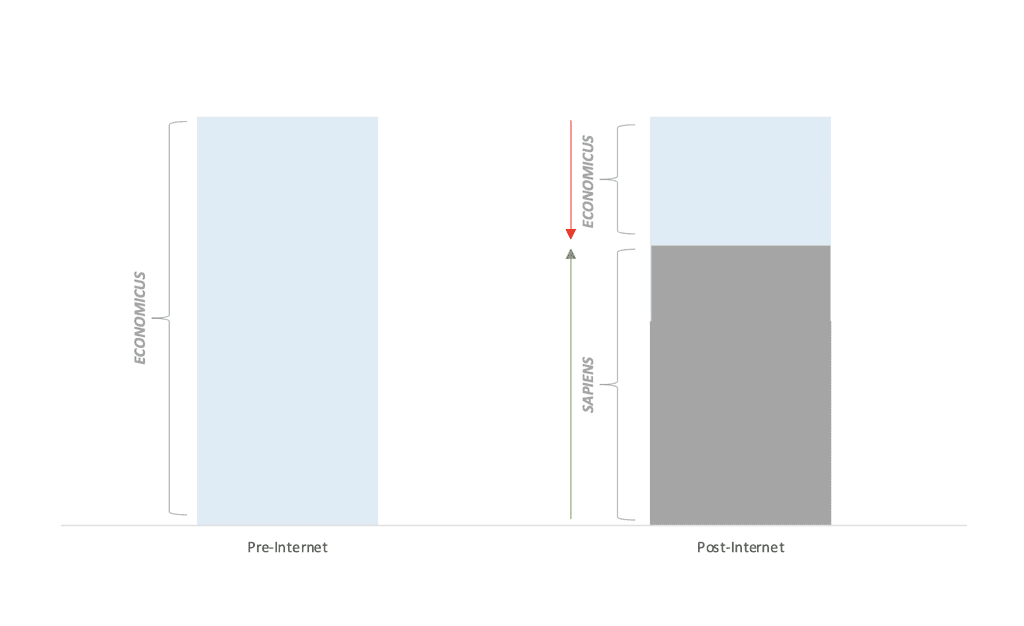

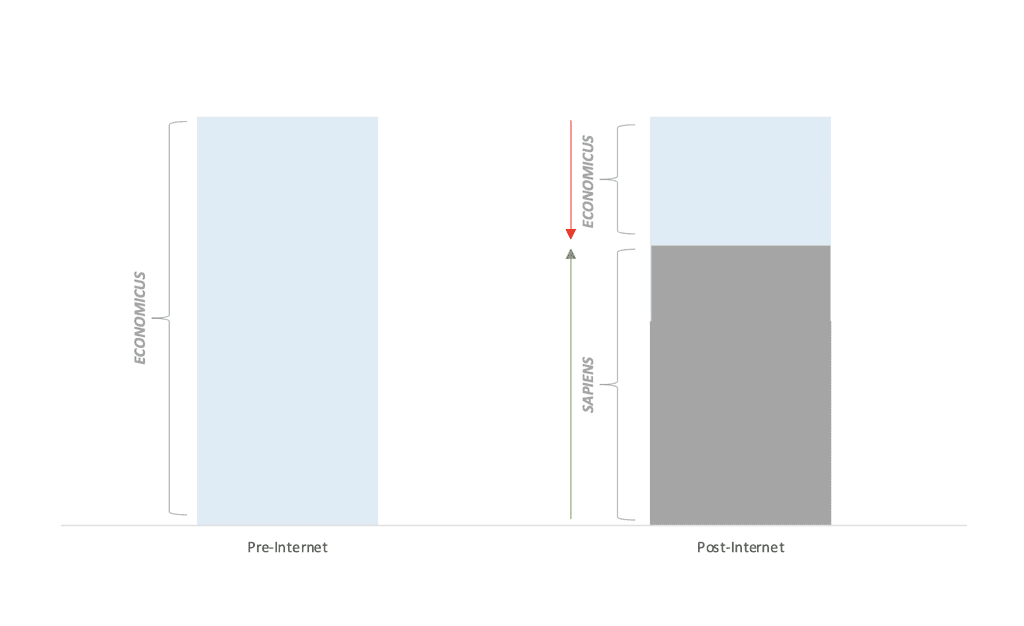

Economicus evolves to Sapiens in the age of the internet. Assuming that total utility remains constant over time, a decrease in Economicus optimization will be substituted by an increase in Sapiens optimization (which we are already starting to see): software eats the world correlates to a Sapiens behavior dominance.

Pre-internet, the most valuable companies engaged in Economicus exchanges. Exxon, GM, Mobil, Ford – I trade value $X for utility Y. There is nothing romantic embedded in these transactions. The swap occurs rationally at a market price for goods set by supply / demand. Oil is likely the strongest example here.

Post-internet, the most valuable companies engage in value swaps that skew more heavily toward Sapiens exchanges. Google, FB, LVMH – the value swaps that occur on these platforms are arguably extremely irrational (trading privacy for convenience, paying more for an item with a logo), yet we willingly engage because they serve us a feeling which we optimize for under a Homo Sapiens framework. That is not to say Economicus disappears entirely; I'd argue Amazon is an example of a utility / profit maximizing framework.

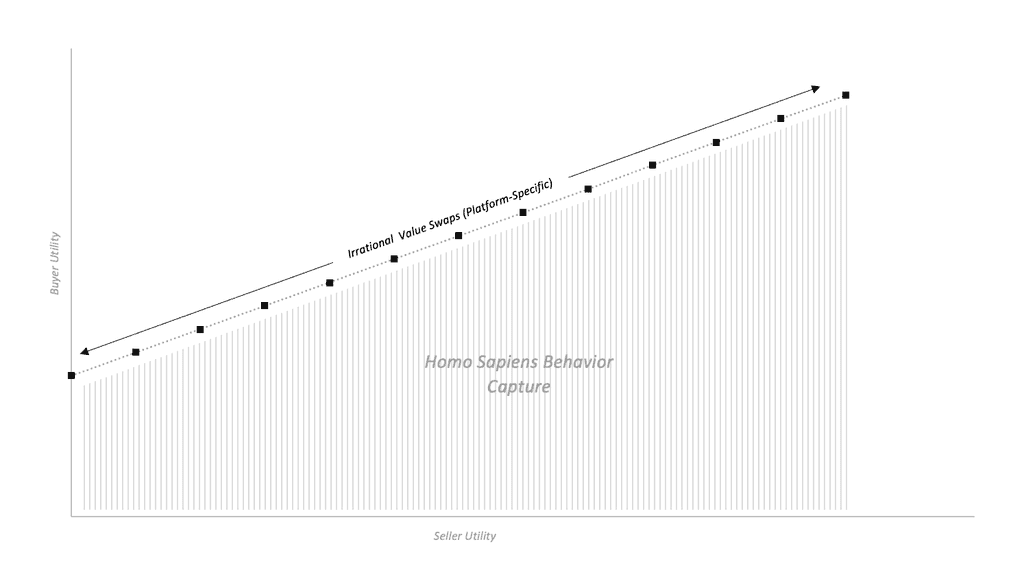

The internet is a sandbox for almost all behavioral economic theory and thus uniquely enables the capture of irrational human behavior at scale. Companies that get people to engage in any series of Sapiens transactions are rewarded an integral the size of that irrationality:

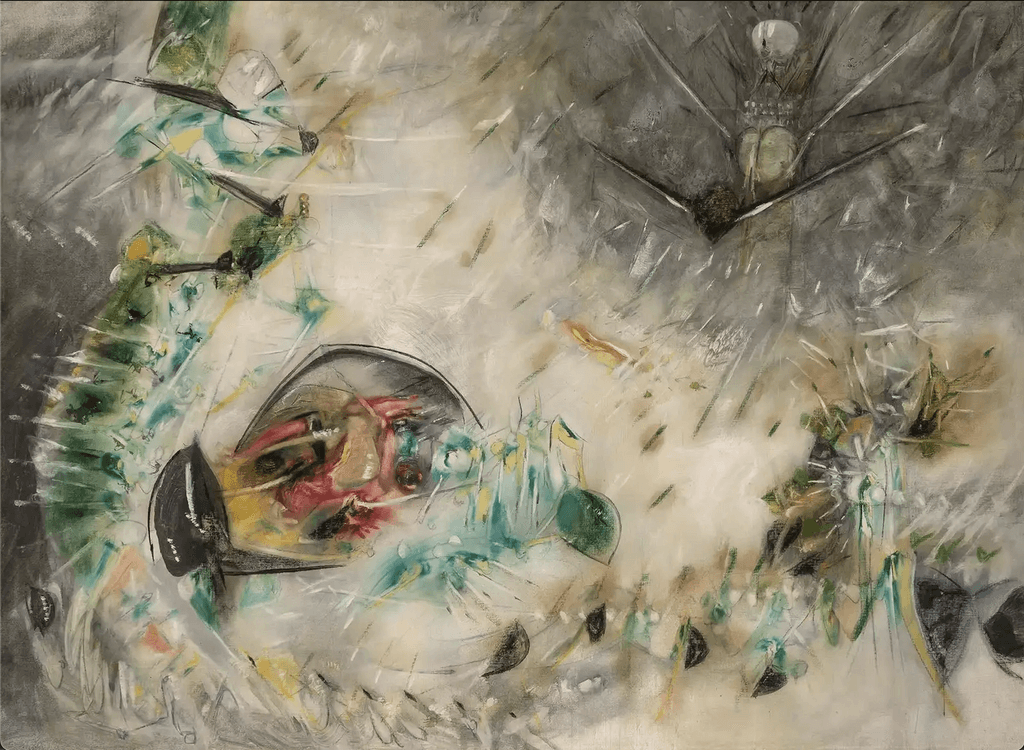

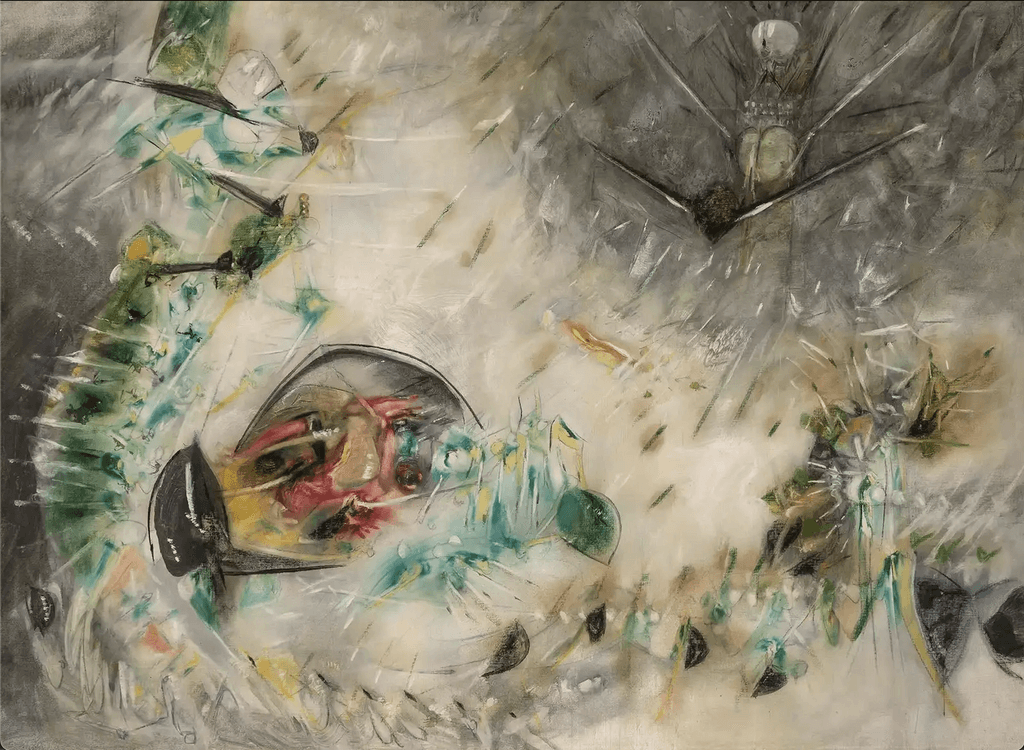

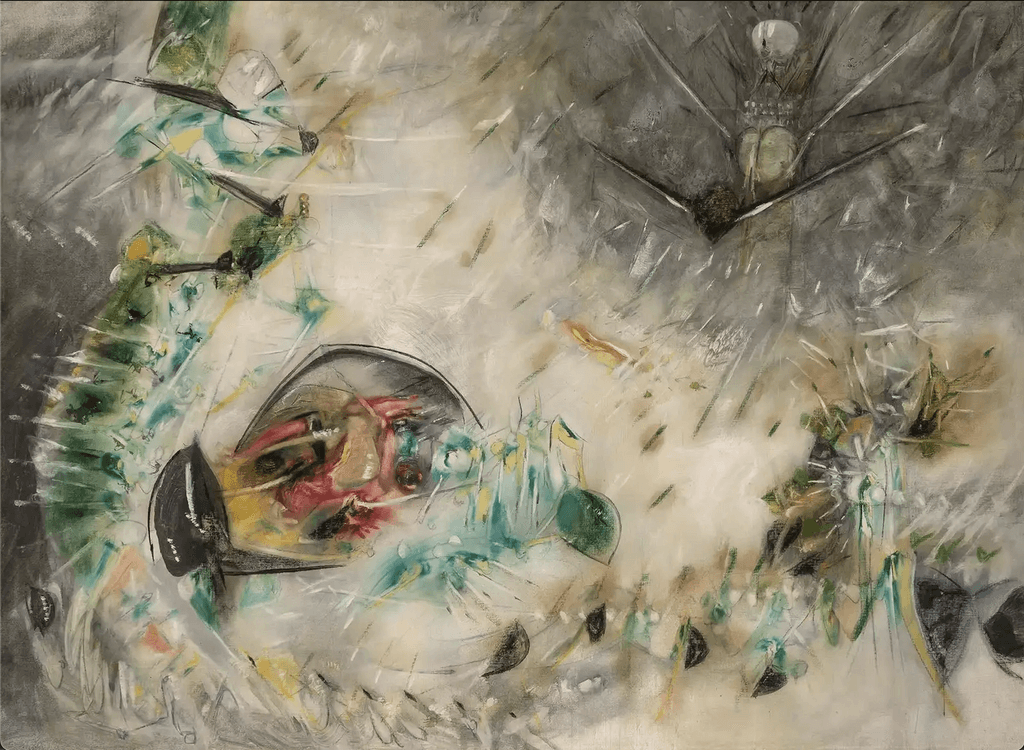

The 50% Irrational in Matter, Roberto Matta (1951)

Some examples of Sapiens behavior on the internet:

Prospect theory / loss aversion: Suggests that people make decisions based on the perceived outcomes of those options rather than the actual utilities. I.e. social proof triggers fear of missing out, so sites show limited quantities of a product available.

Status quo bias (could fall under Prospect Theory): The tendency of people to choose the status quo, even though it may be less favorable than an alternative. People are more likely to stick with what they have instead of taking a risk and switching to something else. Algorithms deeply enable this.

Time preference: The extent to which people value current consumption over future consumption (and are willing to pay a higher amount for the same good). I.e. I am willing to pay more to have something delivered to me today, instead of in a week. Or advertisers optimizing for eyeballs / impressions instead of long-term brand building.

Devaluation of small things that are valuable in aggregate: Small (irrational) transactions which in isolation seem like no big deal, yet once added up are very meaningful. I.e. trading privacy for convenience until your data is everywhere on the web.

When everything is free / accessible / easy, humans will optimize for things other than pure economic utility. So as the cost of software goes to zero, companies must increasingly service Sapiens behavior. I’m not sure where Worldcoin sits on this scale – right now, it seems to be capturing Homo Sapiens behavior with the promise of delivering Economicus value later. We will see how this plays out. What I do not know is whether Sapiens behavior is unique to the human condition while Economicus behavior leans toward the behavior of a machine. How this dynamic starts to change with AI is a theme I am very interested in – I think some of the AI companionship activity (Character, Replica, GirlfriendGPT) hits on this, but not at an equal plane with the reactivity / irrationality of human emotion (not yet at least). Will machines eventually replicate the irrationality of man even if it is not utility maximizing?

According to Blaise Pascal, who you are likely familiar with if you have studied Pascal’s triangle, “the last step of reason is to grasp that there are infinitely many things beyond reason.” There is something to be said that one of the world’s greatest mathematicians / inventors, a type who most strongly prefers scientific / logical reasoning, acknowledges the beauty (and power) of Sapiens behavior, which does not follow the assumed logic of the universe, beyond a purely utility optimizing approach. Lex Fridman has a good podcast on this called Reality is a Paradox (Love and Math).

The 50% Irrational in Matter, Roberto Matta (1951)

I’ve been thinking a lot about rational vs. irrational value swaps lately and where my platform-specific (or not) behavior falls on this plane. As a starting point, these ideas are centered on @cpaik definition of atomic value swaps in his frameworks document:

--

ATOMIC VALUE SWAPS

An Atomic Value Swap is the measurement of the sustainability of repeated core transactions in an ecosystem. Payment for goods or services is an example of an atomic value swap, one where cash is exchanged for an item or service. Both parties deem the transaction to be beneficial and therefore the transaction occurs. If the price of a product or service is too high, the buyer will not engage in the transaction.

Secular to secular (money/goods/services) atomic value swaps are easily understood by the market clearing price of the exchange. Secular to sacred atomic value swaps are significantly more complicated to understand as behavioral psychology tends to skew expected reactions from supply or demand to changes in the transaction.

This extends best to less tangible exchanges as a concept to understand non-monetary transactions. For example, asking for an invitation to a new product is exchanging fractional social indebtedness for a scarce resource.

The three questions that help me ring fence the atomic value swap in any situation are:

What is the value being delivered?

What is the perceived value of what is delivered?

How fairly compensated is the creator for value delivered?

--

Most dominant platforms enable a value swap that is decidedly rational – one that occurs at least on a large enough scale to suggest that there is a clearing price which people are willing to accept in exchange for greater convenience, utility, access, pleasure, etc. In the simplest sense, a user gets something (X) back for what they give away (Y), where they perceive X and Y to be relatively equal. The transaction is fair.

There are other swaps of value which are best characterized as one-sided transactions (in which one party expects nothing or little in return), and if not entirely one-sided, very unequally weighted (highly favorable to one party vs. the other). It is not that these transactions are not fair (they could very well be fair in the mind of the user – the transaction might otherwise not occur), but they do not follow a strictly utility maximizing framework. What drives this type of irrational (and highly willing) behavior is powerful, and appears to be more feeling focused (a “soft” driver of behavior) vs. utility focused (a “hard” driver of behavior). I engaged in a transaction of this nature recently, which informs much of the reasoning I’m attempting to explain in this piece.

The team from Worldcoin was just in New York with one of their orbs (this is Sam Altman’s project premised on a vision for UBI / defi / identity verification in the age of AI). It is at once fascinating, logical and dystopian. Naturally, I wanted to see the orb for myself. World App launched the same week and I could hypothetically tie my identity via iris scan to my wallet. Within a matter of seconds, I conceded my iris and became a number in an index of hashes – for essentially nothing in return, zero utility (outside of the US, there is a token reward for the iris scan… though the tokens are worthless for the time being). I do not necessarily have concerns around privacy in the case of this transaction – the orb generates a unique encoding of the randomness of the iris and destroys the original biometric, aka the iris code is the only thing that leaves the orb. And any transaction in the future is a ZK proof that you are in the verified set, aka identity is never revealed. This is compelling when it comes to human attestation / proof of personhood in an internet increasingly run by AI / deepfakes / bots.

Where I did become increasingly concerned, however, was at my own behavior… how had I so easily engaged in a definitively one-sided value swap – one in which I derived little tangible utility yet willingly relinquished a highly personal, immutable aspect of my own identity. My best explanation of this behavior was something along the lines of tribalism, fear, curiosity and the allure of an aesthetically futurist hardware. None of which should logically justify an uneven swap of value. The crazy thing is I would make this decision again.

Homo Economicus vs. Homo Sapiens theory feels relevant here (and related to the secular vs. sacred concept as referenced in the frameworks document).

Homo Economicus: The figurative human being characterized by an infinite ability to make rational decisions. Narrowly self-interested, Homo Economicus assumes perfect utility / profit maximization.

Homo Sapiens: The figurative human being who is boundedly rational, constrained by limited memory and computational capacity. The decisions made by such humans are influenced by psychological, cultural, and emotional factors.

While Economicus is consistently rational, Sapiens optimizes for a utility that is less quantitatively direct – self expression, social adherence / social signal (where my Worldcoin exchange falls). I think this matches well with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs:

Economicus evolves to Sapiens in the age of the internet. Assuming that total utility remains constant over time, a decrease in Economicus optimization will be substituted by an increase in Sapiens optimization (which we are already starting to see): software eats the world correlates to a Sapiens behavior dominance.

Pre-internet, the most valuable companies engaged in Economicus exchanges. Exxon, GM, Mobil, Ford – I trade value $X for utility Y. There is nothing romantic embedded in these transactions. The swap occurs rationally at a market price for goods set by supply / demand. Oil is likely the strongest example here.

Post-internet, the most valuable companies engage in value swaps that skew more heavily toward Sapiens exchanges. Google, FB, LVMH – the value swaps that occur on these platforms are arguably extremely irrational (trading privacy for convenience, paying more for an item with a logo), yet we willingly engage because they serve us a feeling which we optimize for under a Homo Sapiens framework. That is not to say Economicus disappears entirely; I'd argue Amazon is an example of a utility / profit maximizing framework.

The internet is a sandbox for almost all behavioral economic theory and thus uniquely enables the capture of irrational human behavior at scale. Companies that get people to engage in any series of Sapiens transactions are rewarded an integral the size of that irrationality: